Deconstruction

For so long, I’d made the decision not to decide. My disciplined life walking the proverbial line between gay and Mormon had finally spun in a direction I could no longer control. As depression and resentment began to form the currents of the gyre of my life, any decision seemed better than the fate which lay ahead. In that moment, I was done with it all. With my impending departure for Chile a month away, the time had come to escape my everyday deluge.

For the time being, I was finished with the search for Mr. Right. I was also done with the Church and constant reflection in the misery of my making. For the past year, I’d made every possible effort to make the impossible work, but—like a toppling tower of blocks pulled to precarious station one-by-one—no matter how deliberate my actions or my intentions, the inescapable fate became clearer with each passing moment. Instead of losing, I reinvented my own game.

My life entered an epic of reevaluation. If I wasn’t happy in my conflicted state or even before I realized my homosexuality and lived the life of a faithful Mormon boy, change and growth were the only logical motions. My mind kept returning to the words which seemed so rooted in my conflict—a conflict of happiness in this world versus that in the supposed world to come: “'Life is to be enjoyed, not endured.” These words from the now-deceased prophet Gordon B. Hinckley rang of a universal human love. No sane person wants suffering for himself or others, but that was my state.

Living for pleasure or even relishing the moments as they came had in some ways been ingrained as unproductive and sinful based upon the combination of my drives and upbringing. My father had taught me that not making each moment productive was a form of setting myself up for failure, and while completing one task I should be contemplating the next. The resulting state of constant worry with a constant flux of motivations began to come into question along with a more worrisome question as to the value of life. Fortunately, life had meaning in the sense that suffering was not an end—the same set of blocks, the same ambitions and emotions, the same people and experiences could be reconstructed into something meaningful and even beautiful.

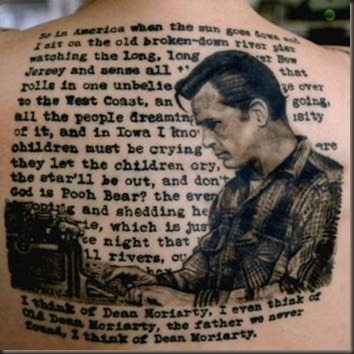

Unemployed and unsure of the future before venturing across the globe to Chile to further contemplate and to teach English, I spent a month attempting to shift gears to a slower pace in life. Unable to find a job before my departure, I spent my days in self-conscious attempts at relaxation: reading, bathing in the sunlight of my back yard, and wrapping my mind around my attempt to escape the faith of my fathers. One morning, fanned by an early summer breeze and smelling of coconut tanning oil, I stumbled upon words I needed in that moment and have guarded ever since.

It was a simple line of poetry by Anton Wildgans: “What is to give light must endure burning.” An obscure Austrian reference that might not have otherwise had impact on me suddenly pulled itself to the forefront. While I’d been taught in religion that the bitter made the sweet sweeter and dark made the light lighter, a certain sense of comfort lay in making suffering somehow less abstract. Though I had no idea what future stood in front of me, I knew that my past, that my caution, that my religion, and my desires of the past twenty-four years would not go to waste.